Characters from the TV series "Derry Girls".

Ireland

In the autumn, we went to Scotland and Ireland. We had met a Northern Irishman who told us that when we came to his country, we shouldn’t miss Giant's Causeway and Carrick-a-Rede. We followed the beautiful north coast and saw the two sites.

The known tourist destinations were breaks in our endeavour to understand the complex political, cultural and religious situation in Ireland and its historical roots.

Giant's Causeway.

Giant's Causeway.

Giant's Causeway consists of impressive tall, angular lava columns standing close in a characteristic pattern.

Carrick-a-Rede is a narrow suspension bridge 23 meters above sea level, used by salmon fishermen to bring their catch ashore from a small rocky island. Now it is crossed by experience-seeking tourists. Hanne refrained, Lars went over, so he can now like our Irish friend say, "I have crossed the Atlantic on foot!"

Carrick-a-Rede.

Carrick-a-Rede.

Peace symbols in Derry and Titanic in Belfast

Clashes between Catholics and Protestants have been going on in Ireland for centuries and did not stop after the division of the country in 1921. Predominantly Protestant Northern Irish Unionists, wish to maintain ties with the United Kingdom, while predominantly Catholic Republicans, wish to unite with the Irish Republic.

During "the Troubles" from 1968 to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, bombs, killings and British tanks in the streets were commonplace in Northern Ireland. Everyone we spoke to hoped that peace would last, but many feared that Brexit could lead to a hard border, economic slowdown, radicalization and new unrest.

Boris Johnson's proposal about a customs border in the Irish Sea was introduced after our visit. Time will tell whether a boundary in water is softer than one on land.

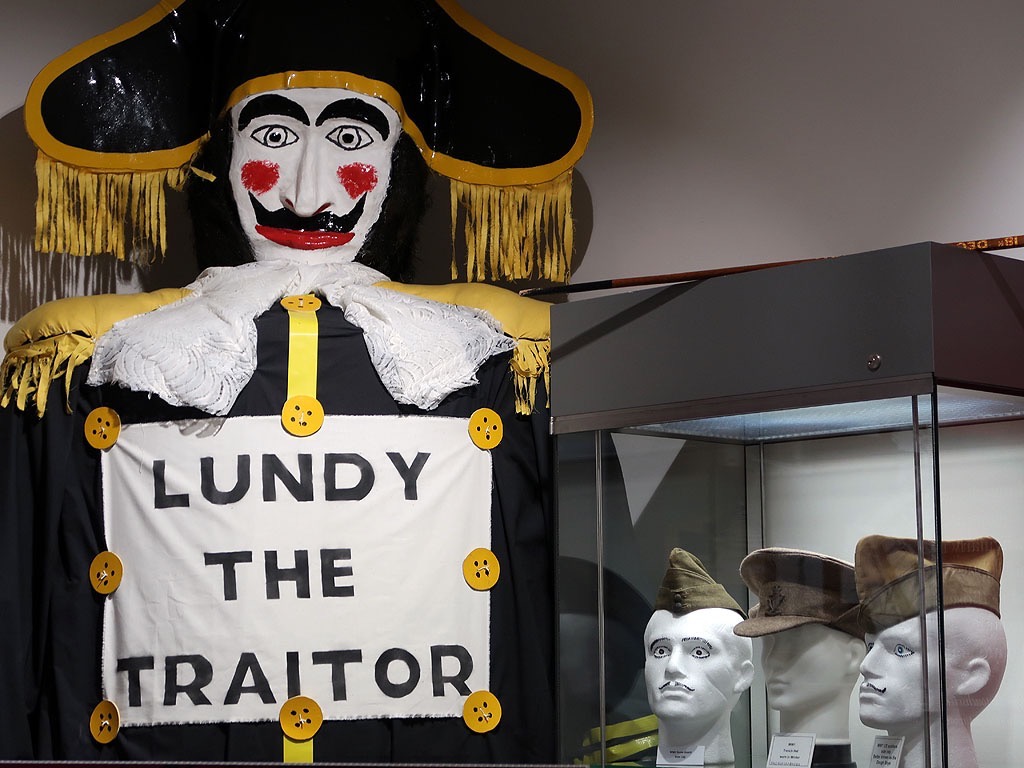

We started in the town called Londonderry by Protestants, among Catholics Derry. We got an overview by walking the city wall dating back to the 17th century. The Siege Museum gave us a Protestant angle on history with the siege by Catholic King James II in 1689 as a focal point.

The Siege Museum.

The Siege Museum.

The Museum of Free Derry gave a Catholic angle with Bloody Sunday in 1972, when British soldiers killed 14 protesters from the US-inspired civil rights movement, as a focal point. A moving documentary told about the events and the joy when Prime Minister David Cameron gave an official apology in 2010.

During a walk in the Bogside neighbourhood where the clash took place and is commemorated in murals, our guide George told his version of the story about Protestant suppression of Catholics. The tour ended at the wall, that originally had the inscription: "You are now entering Free Derry".

Shortly after, we met two young men who called themselves "non-practicing Catholics", their comment was, “It is our grandparents’ and parents’ war, not ours. The war ended in 1998.” They were alarmed by the murder of young journalist Lyra McKee in April 2019.

Mural and the flag of the Irish Republic in Bogside.

Mural and the flag of the Irish Republic in Bogside.

On the tiles of the city's Peace Flame, we read local students' hope of reconciliation, for instance, “We pledge to use: Our lips to respect Difference, Our ears to learn from Others, Our compassion to bring Peace, To make the world a better Place."

Peace Flame.

Peace Flame.

In Belfast, our guide Mark put the Troubles into perspective on a tour to scenes of the conflict. Born in the city and trained as an anthropologist, he works in the company DC Tours.

He gave a committed and balanced introduction to Northern Ireland’s history and current situation. Mark said, “It is not a religious conflict, it is an identity conflict worsened by religion.” Besides arranging tours, the company initiates projects that create dialogue between Protestants and Catholics, for example by inviting them to visit each other's churches.

Mark tells about the Troubles.

Mark tells about the Troubles.

In Derry and in Belfast, we saw high "Peace Walls" with solid gates between Catholic quarters with the Irish Republic's flag waving in green, white and orange, and Protestant quarters where British Union Jack's blue, white and red dominate. A young man thought the fences were now redundant, while people who had experienced the Troubles found them reassuring.

Peace Wall in Belfast.

Peace Wall in Belfast.

We also visited the Anglican Belfast Cathedral with its giant needle-shaped spire. The surrounding neighbourhood is clearly creative. Writers Square has quotes by Irish writers in the tile and is also a scene for cultural and artistic events. At the Mac Metropolitan Arts Centre, we saw fine exhibitions.

Belfast Cathedral.

Belfast Cathedral.

Titanic Quarter is an industrial and working neighbourhood undergoing rapid change into office buildings, creative businesses and fashionable homes. Its flagship Titanic Belfast tells the story about the construction of the Titanic, its shipwreck on the maiden voyage in 1912 and the exploration of the wreck. Built in Belfast, the ship is presented as a product of the flourishing city and British Empire around the turn of the last century. We also saw the exhibition as a still relevant warning of excessive technology optimism.

Titanic Belfast.

Titanic Belfast.

We made a stop at Stormont in Belfast, it houses the Parliament of Northern Ireland, which is a result of the Good Friday Agreement. We talked with people who were frustrated that their parliament had been suspended since 2017. The parties could not agree to form a government. “Important legislation for instance about education can’t be passed,” said one woman in the park. Stormont was reopened in January 2020, while it was suspended, London legalized gay marriage and abortion in Northern Ireland.

Stormont.

Stormont.

Across the border and towards Dublin

During our visit in Northern Ireland, we heard time and again, “We definitely don’t want a hard border.” We also got stories about smugglers of the past and about customs officers who had turned a blind eye. Often followed by humorous plans about how Brexit could create new opportunities for smuggling.

Outside Derry and on our way to Dublin, we experienced the soft border of the Good Friday Agreement. There are no controls and no visible markings except that speed limits and distances on road signs change from miles to kilometres. The currency likewise changes from British pounds to euros, but shops handle both. "The border means nothing now," we were told by a young couple in the border town Newry.

Invisible border at Carlingford Lough.

Invisible border at Carlingford Lough.

Newgrange is an impressive 5000-year-old burial mound, which is part of a larger collection of ancient monuments. There are guided tours to the spot in the inner chamber, which is reached by sunrays on December 21. The significance of spiral patterns carved into some of the large stones still needs to be explained.

Newgrange.

Newgrange.

The Battle of the Boyne Centre tells about the important battle between Catholic King James II and Protestant Prince Wilhelm of Orange in 1690. Wilhelm won the war helped by Danish mercenaries, and afterwards Protestant supremacy in Ireland began. The Centre reopened in 2008, it describes the events in a vivid and balanced manner.

Battle of the Boyne Centre.

Battle of the Boyne Centre.

We had a few days in Dublin. We saw City Hall's exhibition on the city’s history since it was founded by Vikings in the 800s. We visited Dublin City Gallery with Francis Bacon's reconstructed and inspiringly chaotic studio. We went to Dublin Writers Museum with tales of Irish writers and James Joyce as a central figure. We also found a pub with folk music and draft beer in the Latin Quarter Temple Bar.

Next time we will spend more time in the Irish Republic’s inviting capital.

Francis Bacon's reconstructed studio in Dublin City Gallery.

Francis Bacon's reconstructed studio in Dublin City Gallery.

To avoid the forecast hurricane Lorenzo, our ferry departed from Dublin to Cherbourg earlier than scheduled. With the Titanic's fate in fresh memory, it was disturbing, but the captain's course turned out to be wise and we experienced only strong sea near Cornwall. Our tours in the UK ended with passing Lands End again, this time at sea.

January 2020